If you spend enough time around me, I’ll undoubtedly bring up my dad. My childhood centered around him, in a way, because he worked from home during my childhood, and he loved to share his passion for weather (and sports). It’s little surprise that he became a meteorologist. His parents would share how he’d force them to turn the TV to the news each night to ensure he’d hear the daily weather report, even at a young age. In this way, he and I were both lucky. He was lucky in that he was able to achieve a childhood goal of becoming a weatherman, which allowed him to travel, meet plenty of other weather “geeks”, and maintain his favorite hobby, windsurfing. His love for weather was infectious, and it greatly affected my childhood.

I’ll never forget the time in 2003, during Hurricane Isabel’s landfall, he took my brother and I outside to take wind measurements during 70 knot conditions for fun. He’d also take my brother and I on his work trips, which normally involved a drive to someplace on the water, where he’d install, or repair, his company’s equipment, while my brother and I would play until he finished his work. After he’d wrap up, he’d find time to windsurf. I’d surf or bodyboard while my brother normally preferred the beach, building large sandcastles. During these drives, he’d teach us about the weather and while neither my brother nor I became weathermen, we each learned a lot.

One thing I learned was that all weather data in the U.S. comes from a single source, the National Weather Service (NWS).1 If you have an upcoming beach, surf, or scuba session, it’s natural that you’ll check the weather before your trip, right? Should I go to the beach? When? Can I fish today? Is the wind right for me to go kitesurfing? Each of these questions has an answer that depends on the weather. So, regardless of the news site or weather app being used, all that weather data was synthesized and released by the NWS.1

NWS is a part of larger agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which covers a myriad of other roles, such as ocean surveying, managing fisheries, offering funding for coastal and estuarine management, and conducting research.2 It’s difficult to distill the importance of NOAA’s efforts because it covers so many roles, but the easiest way is to discuss weather data because everyone does it.

Beyond day-to-day forecasting, the NWS provides updates on severe weather, tornadoes, wildfires, and hurricane conditions.1 For instance, Hurricane Helene recently slammed into the U.S., landing in Florida, before stalling over the Appalachians, resulting in catastrophic destruction and loss of life.3 Helene’s trail of devastation has been as shocking as it is concerning. Entire towns have been washed away, as a once in a 1,000 year storm brought flooding to areas that were poorly equipped to cope with it.3 There is an additional psychological and longer-term impact that comes from natural disasters, creating trauma and an uptick in mortality for decades.14 However, it’s not just survivors that feel this guilt.

The National Hurricane Center (NHC), a part of NWS, projected the formation of Helene days before it became a formally recognized tropical system in the Gulf of Mexico.10 NHC began mentioning the potential for catastrophic flooding in this region as early as Wednesday, nearly 48 hours before evacuation became an impossibility.10 NWS has workshopped ways to communicate the urgency of threats in its weather alerts, but it’s too difficult to say if Helene could’ve been handled differently.11

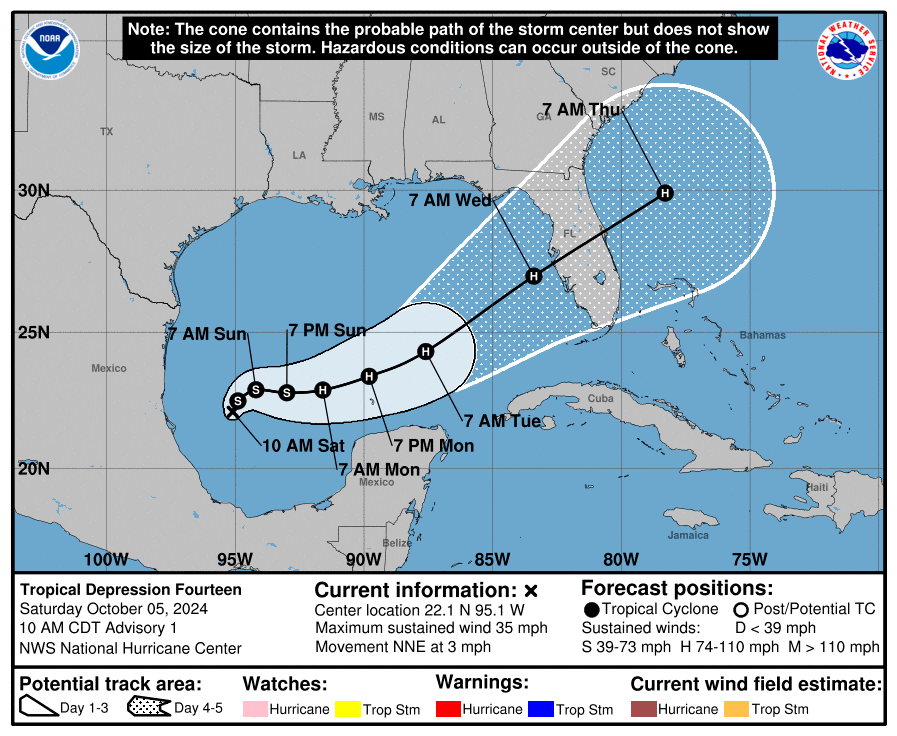

Perhaps the better question for NOAA is how could they have predicted this level of destruction at all? Helene brought an unprecedented flooding to a region that never prepared for this much water.3 It could be a one-off, worst-case scenario, but that appears unlikely. Helene experienced rapid intensification in the Gulf of Mexico, rapidly turning into a major hurricane. Major hurricanes have wind speeds measured as 110 miles per hour or faster. “Rapid intensification” has become a common, worrying concern for additional storms during the peak season.17 In fact, as I’m writing this, Hurricane Milton is beginning its approach to western Florida. Similar to Helene, Milton has gone through rapid intensification and is projected to landfall as a major hurricane.15

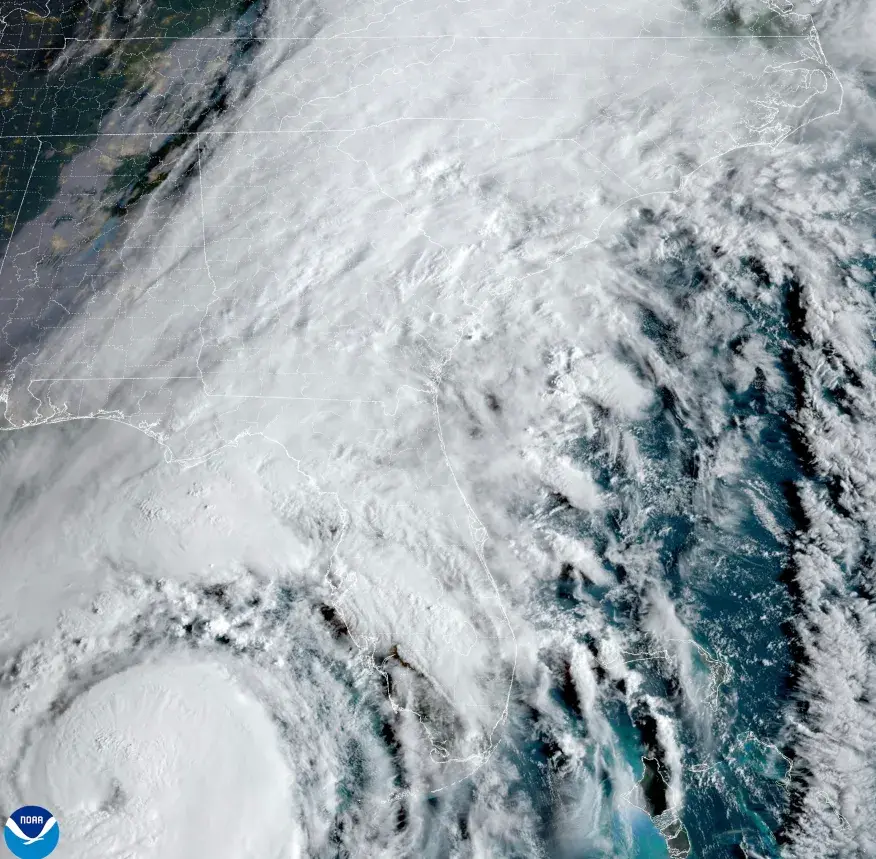

Editors note: Since writing this, Hurricane Milton made landfall just north of Sarasota, Florida as predicted by NOAA on October 10th as a major hurricane. Hurricane Milton underwent rapid intensification, reaching a maximum strength of 897 millibars, making it the 5th strongest hurricane in the history of the American basin. The original forecast above on October 5th for Milton was nearly correct in it's direction and speed several days in advance, however this image shows that the rapid intensification of Milton was somewhat unpredictable and needs to be studied further.

The value of timely, accurate weather data means that it continues to be a target for privatization.6 There have been two previous attempts to privatize functions of the NWS, the first occurring during the Reagan Administration and the second, in 2005, was a failed senate bill aimed at restricting NWS from dispensing weather data for free.

Former President Trump is currently discussing altering the core functions of several offices in NOAA, including the NWS6. In the document, “Project 2025”, published by the Heritage Foundation, the NWS is identified as a target for privatization.7 President Trump has yet to distance his potential second stint in the white house from the ideas discussed in “Project 2025.” In the proposal, the first mention of NOAA states, “The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should be dismantled and many of its functions eliminated.” The paper also states that NWS is “one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry,” and “harmful to future U.S. prosperity”.7

The argument for privatization of weather data is that companies can invest in larger, more complex weather models, and new private weather satellites can be manufactured more cheaply than ever.8 The trouble with that perspective is whether private companies will share their data. Historically, the sharing of global weather data has been a bedrock of the international metrological community.8 As it is today, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which is a part of the United Nations, organizes and regulates the share of weather data internationally, while also contributing to the development of national policy for states that are party to WMO.9 The elimination of NWS could jeopardize the U.S.’s role in this global organization.

Project 2025’s goals for NOAA are summarized here7:

- Reduce budget, staff size for NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research.

- Dismantle the Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, which houses the hurricane hunter program. Hurricane hunters fly into hurricanes to provide accurate data on storm pressure, winds, storm speed, etc.

- Dismantle the National Ocean Service Survey and add ocean surveying to the purview of the U.S. Coast Guard and/or the U.S. Geological Survey.

- Alter how data from tropical systems will be shared with the public.

- Generally, focus NOAA on commercial services.

- Project 2025’s author suggested that weather data should be available for a service charge.

NOAA and NWS provide services beachgoers and hobbyists rely on. Project 2025’s potential changes to NOAA could impact weather data accessibility. With worsening disasters, like Helene, it seems unwise to put time-sensitive weather data behind a paywall, while gutting core functions that help scientists understand natural disasters. Putting weather data behind a paywall also violates the principles of environmental justice, as costs could limit access to weather data for the poor and unhoused. Hardly mentioned in this article is the importance of weather information to farmers, fisherman, blue collar workers, and countless others that make their living outdoors. This government service should remain a government service. It functions as intended and, more importantly, as needed.

References:

- https://www.weather.gov/about/nws

- https://www.noaa.gov/about/organization/noaa-organization-chart

- What Hurricane Helene’s 500-mile path of destruction looks like | CNN

- Twelve years later: The long-term mental health consequences of Hurricane Katrina - PMC (nih.gov)

- Hurricane Helene: Psychological Impacts and Resilience | Psychology Today

- https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/environment/project-2025-paywall-weather/

- 2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf (project2025.org)

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/who-benefits-from-the-privatization-of-weather-data

- https://wmo.int/about-wmo/overview

- Communities need to prepare for catastrophic, life-threatening inland flooding from #Helene, even well after landfall | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (noaa.gov)

- NWS updates extreme cold, freeze alerts ahead of winter | Environment | wfft.com.

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/fact-checking-what-project-2025-says-about-the-national-weather-service-and-noaa.

- As private weather forecasting takes off, who is left behind? | Grist

- How Hurricanes Batter Mental Health | Scientific American

- Impact of Natural Disasters on Mental Health: Evidence and Implications - PMC (nih.gov)

- https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/

- https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutgloss.shtml